A static blog?

Przemysław Kukulski

The idea

In late 2010s static site generators hit the mainstream once again. Quite a surprising turn considering that the tech world generally heads towards interactivity, which is not a strong side of static pages. So... why did that happen? I can think of four possible reasons. First of all, static pages load instantly, as they are pre-rendered and don't contain heavy JavaScript. Secondly, static sites can be hosted cheaply just about anywhere. Another benefit is the lack of maintenance overhead. No security patches and no database backups needed, how does that sound? The last reason, and probably the most relevant one, is nostalgia. Web developers, just like other homo sapiens, can sometimes look at the world through rose-tinted glasses. Serving static HTML files smells like the early world wide web and might feel a bit nostalgic.

Excited by the concept and new tools, I decided to create a personal blog. The first step was to select a framework. I went with Next.js, which seemed appealing mostly because of its use of React.js for rendering. Looking back at it now, it wasn't the best choice. Not because Next is bad, but because generating static HTML is just the tip of the Next.js iceberg. More on that in a second. After finishing my dissertation project, I found time to finish off the blog and work on the content. I'm really happy with the final result and excited to share the insides of the project with you.

Next.js

Next's presence on multiple "top N static page generators" lists might be a bit misleading. While it can output static HTML, the goal of this tool is to serve pre-rendered pages without sacrificing client-side interactivity. It does that by matching routes on the server-side, rendering the initial content, and returning the generated HTML to the client. Scripts included in the markup pull React components and their dependencies to recreate the state of the React app that rendered the page. When that process finishes, React runs as if nothing has happened. This technique is called rehydration and it allows developers to serve useful content without loading screens. What a clever solution!

However, my blog doesn't need rehydration because its pages are truly static. The only thing I am interested in is the output of the initial render. Luckily, Next.js contains an experimental feature that disables rehydration on selected pages. With it, I removed unnecessary scripts and saved around 300kB on the post page. All that's left to do is to render a set of pages to HTML files. This can be done with a few short functions and commands.

Execution

My attempt at creating a blog was heavily guided by the articles below. Check them out if you want to learn about reading and rendering Markdown documents.

- "Creating a Markdown Blog with Next.js" by Kendall Strautman

- "React Markdown — Code and Syntax Highlighting" by Bexultan A. Myrzatayev

Let's take a look at the structure of my blog and examine interesting parts closely.

.

├── README.md

├── package.json

├── next.config.js

├── crop_header.sh

├── crop_post.sh

├── crop.py

├── public

│ └── assets

│ ├── favicon.ico

│ ├── avatar.webp

│ ├── <more public assets>

│ └── type-narrowing-and-closures

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── header-m-1x.webp

│ └── <more post assets>

├── data

│ ├── config.json

│ └── tags.json

├── posts

│ ├── type-narrowing-and-closures.md

│ └── <more posts>

└── src

├── pages

│ ├── _app.js

│ ├── index.js

│ ├── posts

│ │ └── [slug].js

│ └── tags

│ └── [slug].js

├── components

│ ├── PostHeader.js

│ ├── PostFooter.js

│ └── <more components>

├── styles

│ ├── global.css

│ ├── variables.css

│ ├── index.css

│ ├── post-header.css

│ └── <more styles>

└── utils.jsImage processing for responsive images

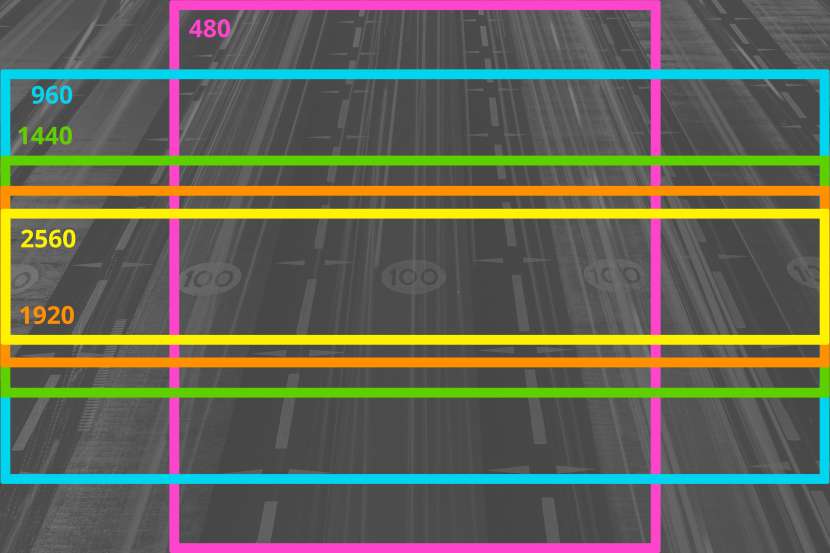

As you know, responsive webpages should adapt to different viewports (mobile, tablet, desktop) and different pixel-density displays. If that was not complicated enough, some browsers don't support modern image formats (yes, I'm looking at you, Safari). Manual cropping, scaling and converting input images, so that they cover all possible scenarios, would take forever. That's why I created a few tools for automating this task. crop.py is a python script for image manipulation. Just like ImageMagic, but with a usable interface 😛. crop_header.sh uses that tool to turn an input header image into multiple variants ready for display on post pages. crop_post.sh is similar but produces images for display in post content.

While crop_post.sh only scales the image, the header cropping script extracts central area an input image maintaining the desired aspect ratio for different viewport sizes.

Here is how I run these two scripts.

bash crop_header.sh ~/input.jpg public/assets/post-slug/

bash crop_post.sh ~/input.jpg public/assets/post-slug/ new-nameAsking the browser to display correct files is quite challenging too. Responsive images article on MDN is an invaluable resource when working with the picture tag and the srcset attribute. The following snippet contains instructions for displaying mobile sized webp header images in two pixel density variants. In the real header component I repeated the source element for all image formats and all viewport sizes!

<picture>

<source

type="image/webp"

media="(max-width: 480px)"

srcSet={`/assets/${slug}/header-s-2x.webp 960w,

/assets/${slug}/header-s-1x.webp 480w`}

/>

{/* more sources here */}

<img

src={`/assets/${slug}/header-m-1x.jpg`}

alt="header image"

/>

</picture>Public assets

public/assets folder contains assets like icons and avatars. Because Next.js copies contents of public folder into the build folder, webpages can reference assets using URLs starting with /assets, e.g. <img src="/assets/avatar.webp" alt="" />.

public/assets/<post-slug> folders store assets used by posts with matching slugs. These are mostly images created by the previously mentioned crop_header.sh and crop_post.sh scripts. README files are for asset credits.

Content

data directory is a place for JSON files with global data used by the blog. config.json stores author data and webpage title. tags.json contains all post tags, as well as their titles and colors. These files are loaded by page components, which will be described later.

posts folder contains my Markdown-formatted posts. The name of a Markdown file is used as a slug in post URLs, e.g. /posts/type-narrowing-and-closures. Every document starts with YAML front matter describing metadata of a post. That metadata lands in many places in the rendered HTML: on post's page, in previews, and head's title, and meta elements.

---

title: "This is my post"

short: "Here is its short description shown in previews."

tags: "javascript,typescript"

published: 2020-01-01

background: "#282828"

---

Document content goes here...Routing

A typical React application decides what content should be shown by matching URL after the app has started. In Next.js, routes are represented by page files and folders inside src/pages. The root page / is rendered by index.js. /hello would try to render hello.js, and nested URLs like posts/first would search for posts/first.js. Simple stuff so far.

Routes can be more dynamic. If a file name contains parameters in square brackets, e.g. tags/[slug].js, it will match many URLs, e.g. /tags/javascript, /tags/react, /tags/next. JavaScript page files can access these parameters and render different content for different URLs.

My blog uses the following files to render posts, tags and the index page.

src/pages/index.js

src/pages/posts/[slug].js

src/pages/tags/[slug].jsHow do we tell Next.js what URLs it should render during a build? Using getStaticPaths function. When exported from a page file, this function tells the "compiler" to render pages with different parameters. The following snippets show how I request the generation of tag pages.

// src/pages/tags/[slug].js

export async function getStaticPaths() {

const tags = (await import('../../../data/tags.json')).default;

return {

fallback: false,

paths: Object.keys(tags).map(slug => ({

params: { slug },

})),

};

}// data/tags.json

{

"typescript": {

"title": "TypeScript",

"color": "#294e80"

},

"markdown": {

"title": "Markdown",

"color": "#000000"

},

// ...

}Pages

Single page applications fetch data from APIs asynchronously. In Next, page components are not rendered until the exported getStaticProps function resolves with page props. This function is a good place to ask an API for data or read files from disk before you render the HTML.

Warning: getStaticProps works only with static generation. For server-side rendering, you need to implement getServerSideProps function.

Here is how I prepare data for post rendering.

// src/pages/posts/[slug].js

import { getPosts } from '../../utils';

export async function getStaticProps(context) {

// extract slug from url

const { slug } = context.params;

// read config, tags and posts

const config = (await import('path-to-config-json')).default;

const tags = (await import('path-to-tags-json')).default;

const posts = getPosts();

// find the post to render + its neighbors

const index = posts.findIndex(post => post.slug === slug);

const post = posts[index];

const nextPost = posts[index-1] ?? null;

const prevPost = posts[index+1] ?? null;

// prepare props

const props = { post, nextPos, PrevPost, config, tags };

// return JSON-compatible version of props

return {

props: JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(props)),

};

};If you're wondering how getPosts function looks like, check this out. It's not that scary! It simply reads posts as text files and separates metadata from content using gray-matter library. Post are sorted by date, so I can show them in a sensible order.

// src/utils.js

import matter from 'gray-matter';

export function getPosts() {

// read files from 'posts' directory

const dir = require.context('../posts', true, /\.md$/);

const fileNames = dir.keys();

const fileValues = fileNames.map(dir);

const posts = fileNames.map((name, i) => {

// slug = name without extension

const slug = name.match(/\/([\w-]+)\.md$/)[1];

// parse text to separate metadata from content

const parsed = matter(fileValues[i].default);

const meta = parsed.data;

const content = parsed.content;

// post = slug + meta + content

return { slug, meta, content };

});

// sort posts by publish date

posts.sort((a, b) => b.meta.published - a.meta.published);

return posts;

}When the data is ready, Post component takes over and generates virtual HTML with post's content. Here is a simplified version of the post component:

// src/pages/posts/[slug].js

export default function Post({ post, nextPost, prevPost }) {

return (

<div>

<Head>

<title>{post.meta.title}</title>

<meta name="description" content={post.meta.short} />

{/* other metadata */}

</Head>

<PostHeader post={post} />

<ReactMarkdown

source={post.content}

renderers={{

code: Code,

paragraph: Paragraph,

image: props => <Image {...props} slug={post.slug} />

}}

/>

<PostFooter />

</div>

);

}ReactMarkdown component from 'react-markdown' library turns my post documents into HTML. Notice how I override default renderers of that element. The paragraph renderer adds additional classes to paragraphs stating with text so that I can style them differently. The image renderer is quite interesting. It creates a figure with caption, making illustrations included in posts look a bit more professional. Furthermore, it renders images with a picture element containing both high and low pixel density images. code, as you might have guessed, renders code snippets with syntax highlighting.

The last piece of the puzzle is disabling rehydration. Hey, do you remember what it is? We can do that by exporting a config object from page components, just like that:

export const config = {

unstable_runtimeJS: false,

};Other code

_app.js

_app.js is an optional file living in pages folder. It's useful for customizing the "React bootstrapping" process. If you want to import global CSS or add head elements, like link, script, or meta, to all pages, this is the right place. Because of Next's early route matching, the application component receives matched page component and props, including URL parameters. All you need to do is render that page, like so:

// src/pages/_app.js

import Head from 'next/head';

import '../styles/variables.css';

import '../styles/global.css';

import '../styles/post.css';

// more css imports here

export default function App({ Component, pageProps }) {

return (

<>

<Head>

{/* favicon, meta, stylesheets, and scripts go here */}

<link href="my-font-source" rel="stylesheet" />

</Head>

{/* render the page */}

<Component {...pageProps} />

</>

);

}Styles

Next.js comes with support for CSS modules (.module.css). Their per-file class name mangling is a great solution to CSS collision problems. While CSS modules can be imported from any JavaScript file, the traditional CSS can only be imported in _app.js. That's exactly where I put all my stylesheets since this project relies on global CSS exclusively.

I must mention the use of CSS variables. For some strange reason, the community has not adopted that technology, despite its high browser compatibility (94.81% of browsers as of 2020-05). In my project, variables describing fonts, font sizes, and colors live in the variables.css file. Styles shared between pages are placed in global.css. All other CSS files are responsible for styling components.

To cope with class collisions and give stylesheets a solid backbone, I followed BEM methodology. Well, with some small modifications. I name BEM components with PascalCase and BEM elements with camelCase. All in all, I am really happy with how styles turned out. My blog looks pretty both in the browser and in the editor!

Components

Separating independent units of the user interface is a common practice in front-end frameworks. It encourages reusability and makes complex applications more manageable. Components of this blog live in src/components folder.

Results and conclusion

The source code of the blog is available on GitHub. Generating truly static and lightweight pages required a bit of effort, mostly because of rehydration, which can be disabled only with the undocumented, experimental feature of Next. All in all, I am happy with the result and will definitely put the blog into use.

Would I use static generation in serious, not "for-fun" projects? Probably not. It's hard to deny that static pages are not very useful these days. Even the most obvious use cases of static site generation, like blogs or documentation pages, benefit greatly from dynamic content such as comments or search results. Maybe it's good enough for static portfolio pages? In the end, if you need to make a hole in a slice of bread, it does not matter if you use your finger, a screwdriver, or an electric drill.

Next.js is not a regular static site generator. It's a framework that brings together the best of three worlds: static generation, server-side rendering, and client-side interactive interfaces. If you think how React applications are usually loaded and run, you realize that with Next's server-side rendering you can speed up the initial render by skipping up to 3 sequential HTTP requests. This is a massive improvement especially for users with a poor internet connection. I would like to see how Next is used in more complex products. Are the benefits worth the transition from pure React? Does Next maintain the separation of back-end logic from user interface logic?